Unanswered Questions in Sri Lanka- MIT Press Blog

Dr. Joe Bock, conflict expert and former early response team member in Sri Lanka, writes about his devastation of the Sri Lanka blasts and the need for early warning to prevent future massacres

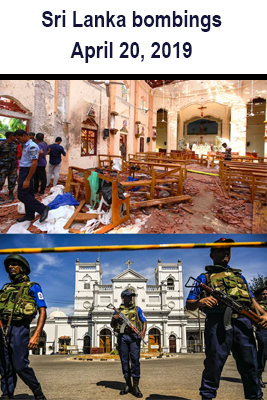

KENNESAW, Ga. (May 6, 2019) — I was dumbfounded on Easter Sunday when I heard about the bombings in Sri Lanka. I worked in Sri Lanka supporting the conflict early warning and early response program of the Foundation for Co-Existence (FCE) during a tenuous cease-fire in 2000–2004. Here, I share some insights that I learned from the staff members of FCE.

FCE had staff in the field, reporting on events of cooperation and conflict. They sent daily reports into FCE headquarters in Colombo. The data were aggregated and analyzed, and when acute tension was evident, FCE issued warnings to a select group of government officials, peacekeeping commanders, UN organizations, and foreign embassies. When it looked like violence was imminent, FCE staff members traveled to the epicenter of acute tension, negotiating between factions, literally putting their lives on the line to save others.

It appears that Sri Lankan government officials issued warnings on April 4—that is, 17 days before the bombings Sunday, April 21. Why wasn’t swift action taken? The short answer is that conflict early warning is much easier than effective early response. Scholars have pointed out how there is a pronounced tendency for there to be a warning-response gap. Why is that? In this case, it is apparently due to:

- Organizational process. The tensions at the highest levels of the Sri Lankan government resulted in convoluted information dissemination.

- Numbness. Security officials in Sri Lanka reportedly receive notices of imminent threats on a regular basis. This can result in “boiled frog syndrome.” When a frog is placed in a pan of cool water, and the water heats up gradually, the frog dies for lack of noticing the gradual temperature change. Whereas a frog would jump out if put in hot water initially. That is why some conflict early warning systems use mathematical pattern recognition to issue warnings when enough data and the patterns of those data indicate that trouble is brewing, as when the water gets dangerously hot for the frog. Mathematical pattern recognition is a hedge against pathologies in collective risk assessment. The math indicates that it is time to jump out of the pot of water even when it doesn’t feel that hot.

- Risk. Deciding to intervene is filled with ambiguity. Sri Lankan officials did not want to cause panic. They did not want to look overzealous, especially vis-à-vis a sensitive religious minority.

In the aftermath of a massacre like this, when the risk of retribution killings is high, we must ask what can be done about incitement communicated via social media. The government of Sri Lanka shut down popular social media sites following the bombings for fear that hate mongering and rumors would result in more bloodshed. This precautionary move is understandable. We have seen that when rumors are disseminated on social media, riots based on identity—both ethnicity and religion—can result in lethal collective action.

Social media is notoriously difficult to monitor for rumors. Automated approaches to identifying rumors are being developed, but they have a long way to go. Essentially, our deep learning is not very deep. We have made advances in how to analyze big data using artificial intelligence for conflict early warning, spotting signals that something destructive is in the works. We have not gotten very far, however, in our ability to identify rumors before they go viral, and rumors are what drive riots. After a disaster like this, when ethno-religious tensions are high, rumors are like a match thrown onto a forest covered in lighter fluid. We can mine data and identify patterns, queue up postings that contain key words and noteworthy sequences, but we are not far enough along in our knowledge of deep learning to be able to distill the meaning of a text, picture, or video.

Do we leave it to Facebook or Twitter and other social media companies to hire enough people to determine what a rumor is when a message has certain key words or when facial recognition shows hatred? Of course we can, but even corporations with deep pockets will find it difficult to stay on top of rumors no matter how many people they are willing to hire and how much they are willing to spend.

Can we ask the “crowd” to report rumors—the segment of the population motivated to keep the peace? If we rely on the crowd, do we put people at risk who forward rumors to authorities? What are the ethics of warning people about potential danger in stifling rumor mongering by militant groups?

There are many open wounds remaining from Sri Lanka’s long civil war, but there is also a huge reservoir of good will. Last Sunday, after hearing about the tragedy, I called a former FCE staff member, the leader of those who intervened in tense situations to prevent bloodshed. He told me that Sri Lankans of all faiths see some of the Catholic Churches as part of their own spiritual home. Non-Christians visit these churches due to a belief in healing powers residing there. He said the churches are symbolic, and that people are communicating that coexistence is what is needed, not division.

I was in Sri Lanka after it suffered a devastating tsunami in 2004. I remember vividly seeing people with very few earthly possessions taking rice, fruit, vegetables, and clothing to tsunami victims in the Eastern Province. The people of Sri Lanka did not ask what someone’s religion was before they helped them. They were actively practicing coexistence then.

These bombings occurred during Easter when people of all faiths celebrated with the island’s Catholic minority. Now, Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, and Christians are donating blood for the victims of the attacks. Will Sri Lankans show restraint and resolve for peace? Will they show us a special kind of interfaith Easter that will be a message to the world?

Joseph G. Bock is director of the School of Conflict Management, Peacebuilding, and Development at Kennesaw State University. He is author of The Technology of Nonviolence: Social Media and Violence Prevention, which was published by MIT Press in 2012. More detail about FCE’s approach to conflict early warning and early response can be found in this book, especially Chapter 5.

Image: FCE staff members in Front of FCE Headquarters in Colombo. Courtesy of Joseph G. Bock.

Original blog appeared on MIT Press.